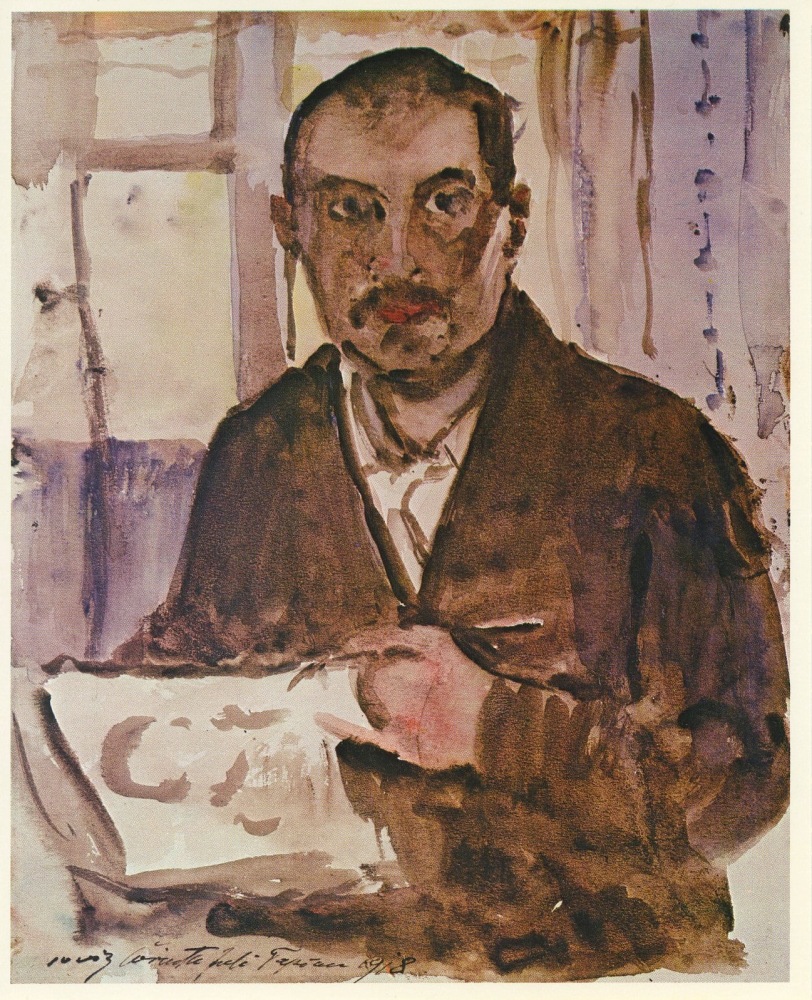

Announcement card for the 1980 exhibition, "German Portrait Drawings" at Allan Frumkin Gallery, New York.

pictured: Lovis Corinth, Self Portrait, 1918, watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 1/2 inches.

When I began working for Allan Frumkin in 1980, I saw myself as an experienced, knowledgeable employee - however I soon realized how much more there was to art, artists and even art making. The diversity and eclectic nature of the gallery’s program at the time frankly baffled me, though I quickly came to appreciate Allan's eye and soon learned from him how to appreciate difficult work. Later we used to say that if you could walk by an artwork without stopping it wasn’t worth your time. Good art, the best art, demanded – commanded – your attention.

Related to this attitude was a side of the gallery that is perhaps not well known but no less central to the gallery’s history and reputation: drawings. Every artist in the gallery, whether painter or sculptor saw drawing as a central part of their work and exhibitions focusing solely on that medium were a mainstay of the gallery's program. I would even go so far as to say Allan’s real strength was his understanding of and appreciation for drawing, and indeed that was his initial focus when he first opened in Chicago in 1952, with drawings by European artists such as Matisse, Beckmann, Corinth, Klee, Leger, Nolde, Matta, Picasso and Giacometti, some acquired directly from the artists' studios. Following the war, many artists who had remained in Europe were only too happy to gain access to an American market and sell directly to a dealer with cash. As a result, those exhibitions from the gallery's first years in Chicago often featured work by European artists, particularly German Expressionists and Surrealists including introductions of work by Alberto Burri, Germaine Richier and others.

During my first year with Allan, when it was quiet on a Saturday morning, I would reach into the closet in his office, select works by these and other artists and ask Allan to explain them to me. I recall in particular thinking Matisse too elegant, being baffled by Corinth’s seemingly indecipherable late work and utterly unmoved by the German Expressionism, one of Allan’s passions – until he patiently showed me how to understand them, and to appreciate, for example, the toughness of Matisse's early drawings, the forcefulness of Corinth’s late work, and the complexity of Beckmann’s compositions. Allan’s eye was not drawn to beauty or elegance but to the challenges a work presented to the artist and to the strategies they employed to surmount them.

I also came to understand that drawing for many artists - beyond an exercise - was the underlying structure of their paintings or even sculpture, and that this was as true for Matisse and Giacometti as it was for most of the contemporary artists the gallery represented, like Robert Arneson, Jack Beal, Joan Brown, Philip Pearlstein, Peter Saul and even H.C. Westermann. Drawing was for many of them a place to experiment or to work out ideas and at the same time a medium in which they could also produce deeply thoughtful, fully realized work. For example in the case of Arneson, drawing was the source of his use of glaze colors and the mark making and textures in his sculpture. For Joan Brown, who almost never made studies for her canvases, drawing was as equally important a medium to her as painting, in that allowed her to work through ideas quickly. And Saul’s work on paper, especially the earliest, were the basis of everything that came after (mostly because he couldn’t afford oils and canvas at the time) - those early canvases are all about drawing.